Abstract

Study design:

Intra-rater reliability study, cross-sectional design.

Objectives:

To report on the intra-rater agreement of the anorectal examinations and classification of injury severity in children with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

Two, non-profit children's hospitals specializing in pediatric SCI.

Methods:

180 subjects had at least two trials of the anorectal examinations as defined by the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to evaluate the agreement. ICC>0.90=high agreement; ICC between 0.75–0.89=moderate agreement; ICC<0.75=poor agreement.

Results:

When evaluated for the entire sample, agreement was moderate-high for anal sensation and contraction and injury classification. When evaluated as a function of age at examination and type of injury, agreement for anal sensation was poor for subjects with tetraplegia in the 12–15-year age group (ICC=0.56) and 16–21-year age group (ICC=0.70) and for subjects with paraplegia in the 6–11-year age group (ICC=0.69). Agreement for anal contraction was moderate for subjects with tetraplegia in the 16–21-year age group (ICC=0.81) and subjects with paraplegia in the 12–15-year age group (ICC=0.78) and poor for subjects with paraplegia in the 6–11-year age group (ICC=0.67). Agreement for injury classification was poor for subjects with tetraplegia in the 12–15-year group (ICC=0.56) and 16–21-year group (ICC=0.74) and paraplegia in the 6–11-year group (ICC=0.11) and 12–15-year group (ICC=0.63). Anorectal responses had high agreement in subjects with tetraplegia in the 6–11-year group and moderate to high agreement in subjects with paraplegia in the 16–21-year group.

Conclusion:

The data do not fully support the use of anorectal examination in children. Further work is warranted to establish the validity of anorectal examination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISCSCI)1, 2 provides a method for the neurological evaluation of persons after spinal cord injury (SCI) and for the classification of the neurological consequence of the injury. The neurological assessments, which include the motor, sensory and anorectal examinations, provide the basis for classifying the neurological level, motor scores and motor level, sensory scores and sensory level, the zone of partial preservation and the degree of impairment or severity of the SCI.

The sensory and motor examination techniques and the classification methodology of the ISCSCI have been well described.1, 2

The anorectal examination involves, in addition to S4-S5 sensory testing, the evaluation of sensation and contraction of the external anal sphincter. For this, the examiner applies pressure with the index finger to the rectal wall (test for sensation) and requests the patient to squeeze ‘as if holding in a bowel movement’ (test for anal contraction). Scoring for both anorectal sensation and contraction is dichotomous (yes/no).

The American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) is utilized to grade the degree of impairment and is based on the sensory and motor function of the sacral segments S4-S5 and the anorectal exam. A complete injury is defined as an absence of motor and sensory function in the lowest sacral level. If there is sacral sparing as evidenced by preservation of pin prick discrimination or light touch sensation in the S4-S5 dermatome, preservation of anorectal sensation or volitional anal contraction, then the SCI is an incomplete injury.

The ISCSCI has undergone several revisions to improve reliability and standardization of both examination and classification techniques.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In their current form1, 2 they allow for consistency in the evaluation and classification of SCI. The majority of psychometric studies have focused on reliability of the motor and sensory examinations,5, 7, 8, 9, 10 but studies of reliability and validity of the anorectal examination have been infrequent.

Methods

Research design

This was a multicenter, prospective study using a repeated measures design. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at both participating sites. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of all participants under 18 years of age. Participants between 7 and 18 years of age also provided written informed assent.

Sample

A sample of 180 participants between 6 and 21 years of age with a chronic SCI (>3 months post injury) were included in this analysis. At the time of the study, all were receiving routine orthopedic and rehabilitation treatment for their chronic SCI. Children were not invited to participate if they had a traumatic brain injury or a condition that limited the ability to cognitively participate in motor and sensory testing.

Data collection

The exam was performed according to the standard ISCSCI methods described above and published elsewhere.1, 2 S4-S5 sensation was tested and scored as a ‘0’ (absent sensation), ‘1’ (impaired sensation) or ‘2’ (intact sensation).

Rectal sensation was evaluated by gently applying pressure to the rectal wall a minimum of three times. Participants who responded ‘yes’ each of the three times were scored as having intact sensation.

Anal contraction was evaluated by gently inserting a finger and asking the participants to squeeze ‘as if to hold in a bowel movement’. During the test of anal contraction, participants were instructed not to increase intra-abdominal pressure by holding their breath or tightening their abdominal muscles.

Each of the participants had a minimum of two neurological exams performed by one examiner, but a maximum of four neurological examinations (two exams each performed by two different examiners). Time between exams ranged from 1 to 3 days. Collectively, there were seven examiners who, before data collection for this study, participated in formal training in the examination techniques12 and classification methodology.11

Data management

Data were de-identified and double-entered into a secure database. The recording of scores was carried out using a customized computer program and statistical analysis was carried out under blinded conditions.

Data analysis

Anorectal sensory and contraction response data were transformed using normalized ranks14, 15 to accommodate binary outcomes. Intra-rater agreement was estimated using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), calculated according to Shrout and Fleiss16 (model 3,k), based on an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures accommodating a nested rater effect and multiple trials per patient. ICC calculations were carried out separately for the entire sample, for three age groups (6–11 years, 12–15 years and 16 years and older) and for type of injury (tetraplegia/paraplegia) by age group. Each ICC is accompanied by the 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS V9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). ICC values of 0.90 and above reflect excellent agreement. Values between 0.75 and 0.89 suggest moderate agreement and those falling below 0.75 are considered poor agreement.17 The 95% CI provides an indication of precision of the coefficients such that a wide CI is considered a low precision.

Results

The sample consisted of 180 participants between 6 and 21 years of age (average age was 14.5 years) with chronic SCI. There were 93 participants with complete injuries and 87 participants with incomplete injuries with a slightly higher number of participants with cervical level SCI (N=91) as compared with participants with paraplegia (N=89). There were 103 males and 77 females with the length of time between date of injury and date of exam ranging from 3 months to 18 years (average was 4.9 years).

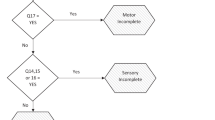

As illustrated in Figure 1, among the 87 participants with incomplete injuries, 38% were incomplete due to intact deep pressure sensation (internal) only; 37% had S4-S5 sparing and intact deep pressure sensation; 18% had S4-S5 sparing, intact rectal sensation and contraction of the external anal sphincter; 4% had intact deep pressure sensation and contraction of the external anal sphincter without S4-S5 sparing; and 3% had S4-S5 sparing only. There were no participants with incomplete injuries due to sparing of only the external anal sphincter contraction or due to the combination of S4-S5 sparing and intact contraction of the external anal sphincter. Among the participants with incomplete injuries, 47% were classified as AIS B, 31% as AIS C and 22% as AIS D; as one of the primary purposes of the study was to examine reliability of the AIS, the AIS designation from the first examination was used to describe the sample.

As shown in Table 1, with all age groups and levels of injury combined, ICC and 95% CI were high for S4-S5 sensation and moderate to good for deep pressure sensation, anorectal contraction and injury severity.

Tables 2 and 3 show ICC and 95% CI for each age group and for each age group with tetraplegia and paraplegia, respectively. As shown in Table 2, for each of the three age groups, there was high agreement for S4-S5 sensation and moderate-to-high agreement for anal sensation, anal contraction and for classification of injury severity. The 95% CI values were also moderate to high, with the exception of anal contraction for the 12–15-year-old group. When stratified by type of injury (tetraplegia/paraplegia) and by age group (Table 3), agreement varied. For the 6–11-year-old group with tetraplegia (N=26), there was perfect agreement for anal sensation and classification of injury severity and high agreement for anal contraction. In contrast, the 6–11-year-old group with paraplegia (N=17) had poor agreement for anal sensation, anal contraction and classification of injury severity. There was poor agreement on classification of injury severity in the 12- to 15-year-age group with tetraplegia (N=17) and with paraplegia (N=32) and in the16- to 21-year-age group with tetraplegia (N=48). In addition, there was poor agreement in classification of anal sensation in those with tetraplegia in the 12- to 15- and 16- to 21-year-age groups.

Discussion

This study evaluated intra-rater agreement of repeated anorectal examinations and classification of injury severity of 180 children and youth with chronic SCI. The study was motivated by the void in the health-care literature on the psychometric integrity of the anorectal examination and our pilot work9, 18 that questioned the utility of the anorectal exam in children.

Agreement on repeated pin prick and light touch sensation at S4-S5 was good for all age groups and type of injury (tetraplegia/paraplegia).

When agreement on repeated deep pressure and anal contraction exams was evaluated for each of the three age groups, there was strongest agreement in the 6- to 11- and 16- to 21-year-age groups with moderate-to-high ICC and lower CI values. The weakest agreement was seen in the 12- to 15-year-age group where, despite ICC values that indicated high-to-moderate agreement, lower CI values for anal contraction and injury severity were poor (0.67) and moderate (0.78), respectively, indicating inadequate precision and weaker agreement for that age group.

When agreement was further evaluated as a factor of type of injury (tetraplegia/paraplegia), the results differed. The youngest age group with tetraplegia had excellent agreement on all the three measures. In contrast, the same age group with paraplegia had poor agreement for all comparisons. This disparity may be attributed to age at injury and level of injury, with reports that young children who sustain tetraplegia, more frequently, have complete injuries.19 Given the relationship between tetraplegia and complete injury in very young children and reports that there is a stronger agreement on repeated exams when there is a complete absence of neurological function,7, 10, 13 our findings reflect factors that have been consistently reported to influence the reliability of motor and sensory testing in children.

Another consideration is age at injury and bowel and bladder continence. We have reported earlier9 that children, regardless of their age at the time of the anorectal exam, who were injured before being toilet trained, may simply not have the necessary experiences or mental representations to respond to instructions such as ‘squeeze as if to hold in a bowel movement’ or ‘tell me when you feel pressure’. In this study, the average age at time of injury for the 6- to 11-year-age group with tetraplegia and paraplegia was 3.7 (s.d.±1.8) and 5.1 (s.d.±3.2) years, respectively. The combination of young age at injury and incomplete lesions in the group with paraplegia may together have contributed to the weak agreement seen in the 6- to 11-year-old group with paraplegia.

For the two older age groups, excluding anal contraction, ICC and 95% values reflected a range in strength of agreement from very poor to moderate with only three of the eight ICC values exceeding the recommended minimum value (0.75)17 for an acceptable outcome measure; these three values reflected only low moderate agreement as evidenced by ICC of 0.8. Such poor agreement and the wide CI in the older age groups were unanticipated and may reflect an issue of not only poor reliability, but also of inadequate validity of the anorectal exam. The issue of reliability pertains to both the systematic and random errors that can commonly occur in measurement. For this study, even though the data collection protocol was standardized, the examiners were trained and the participants had chronic injuries with known neurological stability, some variation may have been attributable to the rater, the participant, the test itself or a combination of all three. However, the magnitude of variation shown by the low ICC and 95% CI values in this study is unlikely an issue of only reliability.

Validity studies have focused on the motor and sensory examinations20, 21, 22 of the ISCSCI, but never on the anorectal examination. Although the invasive nature of the anorectal examination may be a deterrent to studies on reliability and validity, another major reason for the void in studies may be the lack of an alternative method or gold-standard measure to evaluate severity of SCI. We have conducted a pilot investigation18 comparing the ISCSCI and MRI in children with SCI and, among other findings, describe a case where there was MRI evidence of a complete cord disruption, but the participant was classified as incomplete by the ISCSCI anorectal examination.

In earlier work9 and in this study, during the anorectal examinations, participants described a variety of sensations including general warmth throughout their body, head aches, tingling throughout the body and goose bumps. Despite repeated attempts at instructing the participants to respond only when they feel pressure to the rectal wall, they may have been unable to distinguish between deep rectal wall pressure and autonomic sensory responses to the anorectal exam. Children's inability to distinguish between deep rectal wall pressure and autonomic processes may be directly related to their lack of experiences or lack of memory of ‘normal’ sensations and the inability to comprehend deep anal pressure. A recent study by Wietek et al.23 corroborates the reports by participants in this study and showed, by way of FMRI, that alternative pathways are activated during anorectal examination. Collectively, the findings of these studies provide evidence that the validity of the anorectal examination requires further investigation.

The findings from this and other studies 9, 18, 23 have implications on the use of the ISCSCI anorectal examination. First, our data do not fully support the use of anorectal exam with children and youth. Under optimal conditions—a standardized protocol, chronic injuries and the same rater—repeatability of the examinations when evaluated as a factor of age and type of injury was poor. The reasons for the poor agreement are likely multi-factorial and some, such as test instructions, may be modified for children, whereas others, such as validity of the exam, require larger scale studies. Importantly, this study only reports intra-rater agreement and does not evaluate inter-rater agreement.

The second implication of this work relates to the use of the anorectal examination in clinical trials. Paramount to many of the future SCI clinical trials is a valid evaluation tool that generates reliable data on injury severity. Although we recommend further psychometric studies on the ISCSCI anorectal examinations with both children and adults, we also look forward to results of efforts that are focused on establishing a more objective assessment of injury severity, such as diffuse tensor imaging and FMRI.

Last is the implication of this work on the designation of injury severity in children. The classification of injury severity is on the forefront of every parent's mind. It is prudent for those determining and communicating the diagnosis to understand the particularities and the limitations of the anorectal examinations unique to children as described in this study.

Conclusion

This study does not fully support the use of anorectal examinations in pediatrics, but lends support for further research.

References

American Spinal Injury Association. Reference Manual for International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. American Spinal Injury Association: Chicago, 2003.

Marino RJ, Barros T, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns S, Donovan WH, Graves D et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2003; 26 (Supp 1): S50–S56.

Donovan WH, Wilkerson MA, Rossi D, Mechoulam F, Frankowsh RF . A test of the ASIA guidelines for classification of spinal cord injury. J Neuro Rehab 1990; 4: 39–53.

Ditunno JF, Donovan WH, Maynard FM . Reference Manual for the International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. American Spinal Injury Association: Chicago, 1994.

Cohen ME, Sheehan TP, Herbison GJ . Content validity and reliability of the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. Topics SCI Rehab 1996; 1: 15–31.

Cohen ME, Ditunno JF, Donovan WH, Maynard FM . A test of the 1992 international standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 554–560.

Jonsson M, Tollback A, Gonzales H, Borg J . Inter-rater reliability of the 1992 international standards for neurological and functional classification of incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 675–679.

Marino RJ, Jones L, Kirshblum S, Tal J . Reliability of the ASIA motor and sensory examination. J Spinal Cord Med 2004; 27: 194 (Abstract).

Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz RR, Johansen KJ . The international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury: reliability of data when applied to children and youths. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 452–459.

Savic G, Bergstrom EMK, Frankel HL, Jamous MA, Jones PW . Inter-rater reliability of motor and sensory examinations performed according to American Spinal Injury Association standards. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 444–451.

Chafetz R, Vogel L, Betz R, Gaughan JP, Mulcahey MJ . International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury: training effect on accurate classification. J Spinal Cord Med 2008; 31: 538–542.

Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz R, Vogel L . Rater agreement on the ISCSCI motor and sensory scores obtained before and after formal training in testing technique. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: S146–S149.

Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz R . Agreement of repeated motor and sensory scores at individual myotomes and dermatomes in young persons with complete SCI. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 56–61.

Conover W, Iman RL . Rank transformations as a bridge between parametric and nonparametric statistics. Am Stat 1981; 35: 124–129.

Harter HL . Expected values of normal order statistics. Biometrika 1961; 48: 151–165.

Shrout P, Fleiss JL . Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86: 420–428.

Portney LG, Watkins MP . Foundations of Clinical Research. Applications to Practice. 2nd edn. Prentice Hall Health: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2000.

Samdani A, Fayssoux R, Asghar J, McCarthy JJ, Betz R, Gaughan J, Mulcahey MJ . Chronic spinal cord injury in the pediatric population: does magnetic resonance imaging correlate with the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury scores? Spine 2009; 34: 74–81.

Vogel L, DeVivo M . Pediatric spinal cord injury: etiology, demographics, and pathophysiology. Top Spinal Cord Rehab 1997; 3: 1–8.

Crozier KS, Graziani V, Ditunno JF, Herbison GJ . Spinal cord injury: prognosis for ambulation based on sensory examination in patients who are initially motor complete. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991; 72: 119–121.

Burns SP, Golding DG, Rolle WA, Graziani V, Ditunno JF . Recovery of ambulation in motor-incomplete tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 1169–1172.

Marino R, Rider-Foster D, Maissel G, Ditunno JF . Superiority of motor level over single neurological level in categorizing tetraplegia. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 510–513.

Wietek BM, Baron CH, Hinnenghofen H, Badtke A, Kaps HP, Grodd W et al. Cortical processing of residual anorectal sensation in patients with spinal cord injury: an FMRI study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008; 20: 488–497.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Shriners Hospitals for Children Research Advisory Grant no. 8956 (Mulcahey, PI). Louis Hunter, Christina Calhoun, Jennifer Schottler, Beth Lynch and Kim Curran are acknowledged for their assistance with recruitment, data collection and data management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vogel, L., Samdani, A., Chafetz, R. et al. Intra-rater agreement of the anorectal exam and classification of injury severity in children with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 47, 687–691 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.180

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.180

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

What should be clarified when learning the International Standards to Document Remaining Autonomic Function after Spinal Cord Injury (ISAFSCI) among medical students

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2021)

-

An interview based approach to the anorectal portion of the International Standards of Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury Exam (I-A-ISNCSCI): a pilot study

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Pulse article: How do you do the international standards for neurological classification of SCI anorectal exam?

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2017)

-

Measures and Outcome Instruments for Pediatric Spinal Cord Injury

Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports (2016)

-

Analysis of metal artifact reduction tools for dental hardware in CT scans of the oral cavity: kVp, iterative reconstruction, dual-energy CT, metal artifact reduction software: does it make a difference?

Neuroradiology (2015)