Abstract

Introduction

Intracranial carotid artery atherosclerotic disease is an independent predictor for recurrent stroke. However, its quantitative assessment is not routinely performed in clinical practice. In this diagnostic study, we present and evaluate a novel semi-automatic application to quantitatively measure intracranial internal carotid artery (ICA) degree of stenosis and calcium volume in CT angiography (CTA) images.

Methods

In this retrospective study involving CTA images of 88 consecutive patients, intracranial ICA stenosis was quantitatively measured by two independent observers. Stenoses were categorized with cutoff values of 30% and 50%. The calcification in the intracranial ICA was qualitatively categorized as absent, mild, moderate, or severe and quantitatively measured using the semi-automatic application. Linear weighted kappa values were calculated to assess the interobserver agreement of the stenosis and calcium categorization. The average and the standard deviation of the quantitative calcium volume were calculated for the calcium categories.

Results

For the stenosis measurements, the CTA images of 162 arteries yielded an interobserver correlation of 0.78 (P < 0.001). Kappa values of the categorized stenosis measurements were moderate: 0.45 and 0.58 for cutoff values of 30% and 50%, respectively. The kappa value for the calcium categorization was 0.62, with a good agreement between the qualitative and quantitative calcium assessment.

Conclusions

Quantitative degree of stenosis measurement of the intracranial ICA on CTA is feasible with a good interobserver agreement ICA. Qualitative calcium categorization agrees well with quantitative measurements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Various studies have shown that internal carotid artery (ICA) atherosclerotic disease is a strong predictor of ischemic stroke [1, 2]. The majority of these studies focused on the extracranial part of the ICA and the association with intracranial atherosclerotic disease is generally not considered. However, Kappelle et al. [3] have demonstrated that the presence of intracranial ICA atherosclerotic disease is an independent risk factor for subsequent stroke in patients with symptomatic extracranial ICA stenosis. Furthermore, it has been estimated that intracranial arterial disease is responsible for approximately 5–10% or 33–66% of ischemic strokes in the USA and Asia, respectively [4–8]. A third of patients with extracranial carotid atherosclerotic disease has additional intracranial lesions [3]. Because of its tortuosity, the intracranial carotid siphon is a predilection site for early atherosclerotic lesions. Therefore, the presence of atherosclerotic disease in this segment of the ICA may be an important prognostic factor in the prediction of recurrent stroke. Furthermore, reliable assessment of intracranial ICA atherosclerotic disease may influence treatment approach of patients with acute ischemic stroke referred for endovascular treatment. In patients with severe carotid siphon stenosis, thrombectomy with mechanical devices will be more difficult and hazardous than in those without. To definitely establish the significance of carotid siphon disease in future studies, there is an urgent need for accurate and reproducible measurement methods.

Traditionally, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is considered as the gold standard for evaluating intracranial carotid artery stenosis. Presently, DSA is no longer routinely performed in the diagnostic workup of stroke patients, and it is unethical even to apply it for research purposes only because of a small but non-negligible risk of serious complications [9]. Furthermore, DSA does not allow the visualization and quantification of the calcium burden.

Nowadays, noninvasive or minimally invasive tests, such as CT angiography (CTA), are increasingly used in the evaluation of the carotid artery. The diagnostic accuracy of CTA in evaluating intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis compared with DSA has been assessed in previous studies [10–13]. These studies have shown high sensitivity and negative predictive value for detecting intracranial arterial stenosis in CTA as compared with DSA. This makes CTA a potentially useful and accurate noninvasive diagnostic test for detecting intracranial stenosis. However, to our knowledge, the interobserver agreement of the stenosis measurements of the (often severely calcified) intracranial ICA in CTA has not been addressed before.

Reliable analysis of the intracranial part of the ICA remains very challenging. For example, the delineation of the intracranial ICA with CTA causes difficulties because calcifications in the intracranial ICA are in the same intensity range as the skull. Furthermore, there is overlap of intensity of the calcifications and contrast-enhanced lumen [14].

In summary, up to now, there is a lack of studies on the quantitative measurement of the intracranial ICA disease in CTA images. The aim of this study was to present a novel semi-automatic application to quantitatively measure the degree of intracranial ICA stenosis and the calcium volume burden in the intracranial ICA and to assess its interobserver agreement in a population of symptomatic patients.

Methods

Study population

In our center, in the routine diagnostic workup, symptomatic patients suspected of having carotid artery stenosis are primarily evaluated by duplex sonography. Subsequent CTA is performed when a carotid intervention is considered [15]. All consecutive patients who underwent CTA on a 64-section CT scanner for carotid stenosis evaluation between April 1, 2006, and December 31, 2008, were included in the present study. Patients with a previous carotid intervention were excluded. Within a case of an occlusion of the extracranial part of the ICA and of an unreliable reference diameter of the intracranial ICA, the artery was excluded.

Permission of the medical ethics committee was given for this retrospective analysis of anonymized patient data. No informed consent was required because the evaluation of the images was performed outside the clinical setting.

CT imaging protocol

CTA was performed with a 64-slice scanner (Brilliance 64, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands). An 18-gauge intravenous catheter was placed in the antecubital vein, and 80 mL of contrast (Visipaque 320, GE Healthcare) was infused at 4 mL/s after an initial injection delay depending on an attenuation of 150 HU in the aortic arch. Acquisition and reconstruction parameters were as follows: tube voltage, 120 kV; effective mAs, 265; pitch, 0.765; increment, 0.45 mm; slice thickness, 0.9 or 1.5 mm. The thinnest available slice thickness of the CTA images was used. The scan ranged from the aortic arch up to 3 cm above the sella turcica.

Degree of stenosis in the intracranial ICA

We used the Warfarin–Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) method for determining the degree of stenosis in the intracranial ICA [16]. The WASID degree of stenosis is calculated as

The reference diameter is measured at the widest straight part of the petrous segment of the ICA. If the entire petrous part of the ICA is diseased, the most distal parallel part of the extracranial ICA is used as reference.

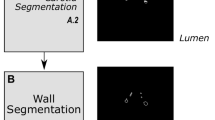

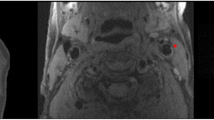

In the CTA images, a central lumen line was created by a single trained observer LB using the 3mensio vascular software (Bilthoven, the Netherlands). The centerline started at the vertical running part of the petrous segment of the ICA closely adjacent to the skull base, which lies in the carotid canal, up to the middle cerebral artery–anterior cerebral artery bifurcation (Fig. 1a). The central lumen lines were inspected independently by two experienced neuroradiologists C.B.M and R.v.d.B.

Views of the semi-automatic software. a Volume rendering view of the CT data including the central lumen line starting at the vertical petrous segment adjacent to the skull base up to the middle cerebral artery–anterior cerebral artery bifurcation. b A view perpendicular to the central lumen line used for diameter measurements; the circle could be adjusted to measure the lumen diameter. c Stretched vessel view providing an overview of the whole running of the vessel, which includes lumen diameters as estimated by the software. d Illustration of the adjustment of the region of interest of the calcium volume measurement, which can be performed with the circular contour editor. d Calculated calcium voxels, which are the voxels with an intensity above a threshold value (of 420 HU) within the region of interest

The centerline was used to generate additional views of the intracranial ICA for the vessel analysis: a stretched vessel view, producing an overview of the whole running of the artery, and a perpendicular view, generating a view of the artery orthogonal to the centerline (Fig. 1b).

Subsequently, the observers independently measured the degree of stenosis, blinded for clinical information. To determine the degree of stenosis, the smallest diameter of intracranial ICA up to the vertical running of segment C7 in the internal carotid artery classification of Bouthillier [14] and a reference diameter of the intracranial ICA was manually measured on the view perpendicular to the running of the vessel. In a separate session with both observers before the actual measurements, it was mutually agreed that the diameter was defined as the shortest cross-section through the center of artery. Due to the high density of calcified plaques, these may appear larger in CT images due to the so-called blooming artifact. Both observers were aware of these blooming artifacts and performed the diameter measurements while optimally correcting for these artifacts. Window/level settings were set to 750 HU (width) and 200 HU (level), but the observers were allowed to adjust these settings.

We excluded the C7 segment of the intracranial ICA because the diameter of the intracranial ICA commonly reduces after the origin of the posterior communicating artery. Including the diameter of the C7 segment may introduce pseudo-stenosis even in healthy arteries.

Following Nguyen-Huynh et al. and the WASID trial, we categorized the stenosis in the intracranial ICA as either smaller or larger than a cutoff of 30% and 50% [10, 17].

Intracranial calcium volume

Using the additional generated views, the intracranial ICA was reviewed to detect calcifications in the artery wall. Based upon the visible amount of high-intensity voxels in the CT images, the arteries were qualitatively labeled as absent, mild, moderate, or severe by two independent observers C.B.M and R.v.d.B. Before the scoring sessions, a joint meeting was organized in which the observers agreed upon the method and measures of classification.

A single observer L.B. measured the volume of the calcium burden quantitatively with the 3mensio software of all arteries. Using the central lumen line as determined for the stenosis measurements, the segment of the central lumen line that contained calcifications was selected. A region of interest was generated in this selected segment, which could be manually adjusted in the perpendicular view (Fig. 1d). Since the calcifications were often closely adjacent to the skull base and the HU values of the skull are in the same range as the calcified plaques, the skull was manually removed from the region of interest. A threshold value for calcifications was set at 420 HU to successfully separate the calcified voxels from the contrast-enhanced lumen. Subsequently, the software automatically calculated the volume of the voxels (in cubic millimeters) above this threshold in the defined region of interest (Fig. 1e). The semi-automatically segmented voxels were displayed in the software, subsequently checked for errors, and manually adjusted if required. Because the volumetric calcium calculation is fully automatic and the delineation of the calcium from the skull was the only manual interaction, only limited user dependence was expected. Therefore, the interobserver variability of the calcium measurement was assessed using a subset of 20 consecutive patients.

Statistical analysis

The Pearson correlation coefficient r was calculated to estimate the interobserver agreement. To estimate the statistical significance of the Pearson correlation coefficient, the P value was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t test; 95% confidence interval (CI) values were calculated. Using linear weighted kappa statistics, interobserver agreement of the categorized stenosis measurements (cutoff values, ≥30% and ≥50%) was determined. Interobserver differences in calcium volume classification (absent, mild, moderate, or severe) were presented with the linear weighted kappa. The following as standards for strength of agreement for the kappa coefficient were applied: <0.00 = poor, 0.00–0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = substantial, and 0.81–1.00 = almost perfect [18]. The correlation of the semi-automatically quantified calcium volume measurement and calcification categorization of a single observer L.B. was presented as the mean ± SD. Both arteries of each patient were considered independent from each other in the analysis.

Error analysis

To evaluate possible causes of disagreement of the interobserver stenosis measurements, we selected stenosis measurements that differed more than 15% from the two observers. We classified the errors as: (a) differences in reference diameter, (b) different position of the site of maximal stenosis, and (c) different measurement of the minimal diameter. Scatter plots of the differences in stenosis measurements as a function of minimal diameter or reference diameter were generated.

Results

Eligible CTA images of 88 patients were available. Sixty percent of patients were male and the mean age was 67 years (SD = 12). The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The CTA tests yielded images of 176 available arteries for our analyses. Thirteen arteries were excluded because of occlusion of the extracranial ICA. One artery was excluded because of an unreliable reference diameter of the ICA.

The scatter plot of the stenosis measurements is shown in Fig. 2. The Pearson correlation coefficient r was 0.78 (95% CI = 0.71–0.83, P < 0.001). With a cutoff at 30% stenosis, the interobserver agreement measured by the linear weighted kappa was 0.45 (95% CI = 0.28–0.62). With a taken 50% stenosis cutoff, kappa was 0.58 (95% CI = 0.45–0.71). The mean difference of the degree of stenosis measurements was 9.2 ± 7.7%. The interobserver agreement expressed as the linear weighted kappa of the qualitative categorization of the calcium volume was 0.62 (95% CI = 0.54–0.70).

The relation between the qualitative and quantitative calcium score is illustrated in Fig. 3. The agreement of the quantitative and qualitative scoring of the calcium volume of arteries labeled as absent calcium was perfect with a mean volume of 0 ± 0 mm3. The mean calcium score of the mildly calcified vessels was 31 ± 37 mm3, and the vessels that were qualified as moderate calcified vessels had a mean calcium score of 113 ± 76 mm3. The vessels that were qualified as severe calcified had a mean of 288 ± 162 mm3 calcium. The interobserver agreement of the semi-automatically quantitative calcium score was excellent, with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.99 (P < 0.01) with a 95% limit of agreement of 0.3 ± 8.5 mm3.

Correlation between the qualitative and quantitative calcium score. The boxes show the mean quantitative calcium score (in cubic millimeters) per calcification category; the whiskers show the standard deviation. The mean quantitative calcium scores in the absent, mild, moderate, and severe groups are 0 ± 0, 31 ± 37, 113 ± 76, and 288 ± 162 mm3, respectively

Error analysis

Eighty-five percent of the measured degree of stenosis had a difference in stenosis measurement of 15% or less between the two observers. Of the arteries with larger differences, 7 had a relatively large difference in reference diameter, 15 arteries had a different position of the site of maximal degree of stenosis, and a different measurement of the minimal diameter was observed in 9 arteries. Absolute differences in the stenosis measurements did not depend on the size of mean reference diameter or mean minimal diameter (Fig. 4).

Discussion

We have presented a novel semi-automatic application to quantify the intracranial ICA stenosis and calcification on CTA images. A good interobserver agreement for the stenosis measurement was obtained, with a moderate kappa and an average difference smaller than 10%. The interobserver agreement of the qualitative calcium classification was substantial. The qualitative classification of the calcifications in the intracranial ICA agrees well with the quantitative calcium volume measurements.

There is increasing evidence that the quantitative assessment of intracranial atherosclerotic disease is of great importance for prognostics and treatment decision. Since the 1980s, it is known that stenosis of the intracranial ICA carries an increased risk of stroke [19, 20]. In a systematic review to assess the impact of potential risk factors other than compromised cerebral blood flow, it was found that patients with intracranial ICA stenosis or occlusion have a higher rate of recurrent stroke (rate ratio, 1.09; 95% CI = 1.05–1.14) than patients with extracranial carotid or middle cerebral artery stenosis or occlusion [21].

The incidence of symptomatic cerebral ischemia as results of in-tandem stenosis (extracranial ICA stenosis with ipsilateral intracranial ICA stenosis) has been estimated between 20% and 50% [22]. Events distal to severe ICA stenosis can result from hemodynamic impairment. Hemodynamic stroke can be caused by severe obstruction of the intracranial ICA. The study of Moustafa et al. [23] supported the idea that in symptomatic carotid disease, deep watershed infarcts result from hemodynamic impairment secondary to severe lumen stenosis or from microembolism secondary to plaque inflammation. Decision making for treatment may need to take the hemodynamic situation of in-tandem stenosis into account. Carotid endarterectomy has been reported to have an increased perioperative risk in the presence of carotid siphon stenosis [24, 25]. Cohen et al. [26] have shown that the characteristics of intracranial stenoses determine the feasibility of the endovascular procedures. Alternative treatments have been suggested such as simultaneous stenting of intra- and extracranial carotid artery or a combined extracranial endarterectomy and intracranial angioplasty [27, 28].

The interobserver variability of intracranial stenosis measurement has been addressed by a few previous studies. In a group of patients suspected of acute cerebral ischemia, Nguyen-Huynh et al. [10] measured the intracranial stenosis in which 93.3% and 90.5% of the vessel segments had an error smaller than 10% for DSA and maximum intensity profile thin slab images of CTA, respectively. In our study, 85% of the stenosis measurements had a difference smaller than 15%. This difference in performance may be caused by the inclusion of multiple intracranial vessel segments in the stenosis measurement instead of only the most severe. Bash et al. [11] showed a high interobserver agreement for the stenosis measurement in 28 patients using the NASCET criteria in 24 segments per patient, resulting in a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.95 (95% CI = 0.93–0.96). Homburg et al. [29] showed a good interobserver agreement with a kappa of 0.79 (95% CI = 0.55–1.00) in intracranial stenosis categorization arteries excluding the carotid siphon in the CTA images of 50 patients. The somewhat lower correlation values that we find may indicate that the degree of stenosis of the intracranial ICA is more difficult to measure than the other intracranial vessel segments.

In a previous study, the interobserver agreement of a manual stenosis measurement of the extracranial ICA was calculated with a comparable Pearson correlation coefficient, r = 0.86 (95% CI = 0.76–0.92), on the same patient group [30]. Similar results were obtained with correlation coefficients of 0.60, 0.77–0.79, and 0.90 [31–33]. For (semi-)automated analysis, the correlation improved with correlation coefficients of 0.96 (95% CI = 0.95–0.96), 0.93, and 0.90 [30, 31, 34]. Kappa values for stenosis categorization of the extracranial stenosis vary considerably, ranging from 0.48 to 0.93 and from 0.65 to 0.93 for manual and automated stenosis measurements, respectively. The kappa values that we determined for the intracranial stenosis measurements are in the low end of this range. The somewhat lower kappa values can be associated with scattering of the stenosis measurements around the cutoff points of 30% and 50% stenosis.

Measurement of the calcification in the intracranial ICA has been addressed in previous studies with either qualitative categorization [35, 36] or quantitative measurements [37, 38]. However, the interobserver agreement and correlation between quantitative and qualitative calcium measurements was not considered previously. The quantitative calcium measurement is semi-automatic. Only the separation of calcium in the vessel wall from the skull was performed manually. Therefore, a high interobserver agreement was expected and a smaller population of 20 patients was used to assess this agreement. With a Pearson’s correlation of 0.99, it was shown that the interobserver agreement was indeed excellent.

The calculated calcium volume may depend on the threshold that was used. In the literature, this threshold varies severely from 130 HU in non-contrast CT images of the coronary arteries [39] up to 800 HU in the CTA of the aortic root [40]. The threshold should be set to a value that accurately separates calcium from the contrast-enhanced lumen. The threshold of 420 HU was empirically determined in a subset of the images before the actual measurements were performed.

We observed a good correlation of the qualitative calcium scoring with the quantitative calcium volume measurements, which is reassuring. This means that no bias can be expected when either one is chosen in diagnostic studies. In this study, we addressed the quantitative volume measurements because we expect that intracranial calcium volume will play an important role in future risk assessment in patients with stroke.

Fifteen percent of the stenosis measurements between the two observers differed more than 15%. A smaller interobserver agreement of these measurements as compared with extracranial stenosis measurements could be expected. With the small diameters of the intracranial ICA with reference diameter ranging between 2.3 and 6.7 mm, in combination with the limited resolution of about 0.5 mm, small errors in a measurement may result in a large difference in the degree of stenosis calculation. However, in our study, no direct relation between smaller reference diameter or minimal diameter with difference in stenosis measurement was found. Along the course of the intracranial ICA, there are relatively large variations of the diameter, which makes it more difficult to obtain reproducible reference diameters. We tried to reduce interobserver variations by choosing the site of the largest diameter in the horizontal petrous part of the internal carotid artery as the reference diameter.

In a recent study, it was shown that volume rendering and maximum-intensity projection techniques provide the optimal interobserver agreement for intracranial stenosis measurement [41]. However, for intracranial ICA, these techniques are suboptimal due to the present adjacent skull. The software used in this study produced a stretched vessel view based upon the centerline. This view enabled an overview of the whole vessel in a single view, which facilitated the identification of the area with the smallest diameter. The cross-section view of the vessel made it possible to accurately measure the diameter.

Carotid siphon calcifications have predictive values with respect to systemic disease [42]. Furthermore, Hong et al. [36] found a correlation between the degree of carotid siphon calcification and the occurrence of lacunar infarction. The software enabled a rotation around the vessel, facilitating an overview of the calcification of the vessel. Because the intracranial ICA is closely adjacent to the skull and the intravascular contrast enhancement is in the same range of HU as the calcifications, it is difficult to measure the calcifications. With the software, we could manually adjust the region of interest by removing the skull out of this region of interest. This quantitative calcium measurement was rather time-consuming due to the manual editing.

A limitation of the present study is that the quantitative calcium volume measurement is not fully automated and can be rather labor-intensive due to the manual editing. The analysis required placement of seed points for the generation of centerlines, manual diameter measurements, and a separation of the calcifications from the skull. It was estimated that it lasted approximately 3–4 min per vessel to generate the central lumen line per vessel. The degree of stenosis measurement was performed in 1–2 min per vessel. The semi-automatic quantitative calcium measurement was performed in approximately 10 min per vessel.

Another limitation of the current study is that we could not estimate the diagnostic accuracy by comparison with a gold standard because performing DSA in all patients, for research purposes, is not ethical anymore. However, the accuracy in stenosis measurement of intracranial arteries in CTA as compared with the gold standard DSA has previously been demonstrated in previous studies [10–13]. These studies showed a good correlation between CTA and DSA measurements. Since the actual measurement was comparable to these previous studies, we assume a similar accuracy of the stenosis measurements in this study.

Also, the accuracy of the calcium volume measurement was not assessed. Calcium volume measurements are based on straightforward thresholding techniques in which the voxels with intensities higher than a threshold are counted and weighted. This technique was introduced in the early 1990s and is routinely performed in clinical practice to assess the calcium burden in coronary arteries [39]. The validation of this technique is still subject of research even 20 years since its introduction [43]. In 1995, Rumberger et al. confirmed an intimate relationship with histologically observed atherosclerotic plaque volume and calcium volume scores on CT images [44, 45]. Since then, it was shown that calcium score is a good indicator of the extent of atherosclerotic disease [45]. More recently, it was shown that calcium volume measured on CTA also strongly correlates with the original Agatston score on non-enhanced CT images [46].

The spatial resolution of CTA is limited with a 0.9-mm z-axis resolution and an average axial resolution of 0.3 mm. In small vessels with a diameter <3 mm, a small difference in diameter measurement may result in a considerable difference in degree of stenosis. Although both observers have more than 10 years experience in measuring the degree of stenosis in CTA images, the intracranial ICA stenosis is not measured on a routine basis in CTA, and this study may suffer from a learning curve effect.

We expect that advanced image processing algorithms may decrease the analysis time and increase the interobserver agreement. For example, matched masked bone elimination results in an image of the intracranial artery tree without the skull [47]. On such an image, it is easier to segment the arteries and to automatically generate a centerline. Subsequently, the position of minimal diameter and the amount of calcification could be determined. It has been shown that such automations result in an increase of interobserver agreement and a reduction in analysis time.

Conclusion

We have presented and evaluated a semi-automatic method to quantitatively measure the degree of stenosis and the calcification volume in the intracranial ICA. A good interobserver agreement was obtained for the stenosis measurements and a substantial interobserver agreement for qualitative calcium categorization. By providing reproducible quantitative assessment of intracranial internal carotid disease, this method may be used in risk assessment in the near future.

References

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators (1991) Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 325(7):445–453. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108153250701

MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) (1998) Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results. Lancet 351(9113):1379–1387

Kappelle LJ, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Sharpe BL, Barnett HJ (1999) Importance of intracranial atherosclerotic disease in patients with symptomatic stenosis of the internal carotid artery. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trail. Stroke 30(2):282–286

Thajeb P (1993) Large vessel disease in Chinese patients with capsular infarcts and prior ipsilateral transient ischaemia. Neuroradiology 35(3):190–195

Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, Zamanillo MC (1995) Race-ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke 26(1):14–20

Wityk RJ, Lehman D, Klag M, Coresh J, Ahn H, Litt B (1996) Race and sex differences in the distribution of cerebral atherosclerosis. Stroke 27(11):1974–1980

Wong KS, Huang YN, Gao S, Lam WW, Chan YL, Kay R (1998) Intracranial stenosis in Chinese patients with acute stroke. Neurology 50(3):812–813

Wong KS, Li H (2003) Long-term mortality and recurrent stroke risk among Chinese stroke patients with predominant intracranial atherosclerosis. Stroke 34(10):2361–2366. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000089017.90037

Willinsky RA, Taylor SM, TerBrugge K, Farb RI, Tomlinson G, Montanera W (2003) Neurologic complications of cerebral angiography: prospective analysis of 2,899 procedures and review of the literature. Radiology 227(2):522–528. doi:10.1148/radiol.2272012071

Nguyen-Huynh MN, Wintermark M, English J, Lam J, Vittinghoff E, Smith WS, Johnston SC (2008) How accurate is CT angiography in evaluating intracranial atherosclerotic disease? Stroke 39(4):1184–1188. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.502906

Bash S, Villablanca JP, Jahan R, Duckwiler G, Tillis M, Kidwell C, Saver J, Sayre J (2005) Intracranial vascular stenosis and occlusive disease: evaluation with CT angiography, MR angiography, and digital subtraction angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 26(5):1012–1021

Ferguson SD, Rosen DS, Bardo D, Macdonald RL (2010) Arterial diameters on catheter and computed tomographic angiography. World Neurosurg 73(3):165–173. doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2008.12.017, discussion e125

Villablanca JP, Rodriguez FJ, Stockman T, Dahliwal S, Omura M, Hazany S, Sayre J (2007) MDCT angiography for detection and quantification of small intracranial arteries: comparison with conventional catheter angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188(2):593–602. doi:10.2214/AJR.05.2143

Morhard D, Fink C, Becker C, Reiser MF, Nikolaou K (2008) Value of automatic bone subtraction in cranial CT angiography: comparison of bone-subtracted vs. standard CT angiography in 100 patients. Eur Radiol 18(5):974–982. doi:10.1007/s00330-008-0855-7

Wardlaw JM, Chappell FM, Best JJ, Wartolowska K, Berry E, Best JJK, Research NHS, Development Health Technology Assessment Carotid Stenosis Imaging G (2006) Non-invasive imaging compared with intra-arterial angiography in the diagnosis of symptomatic carotid stenosis: a meta-analysis. Lancet 367(9521):1503–1512

Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, Smith HA, Chimowitz MI (2000) A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 21(4):643–646

Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, Stern BJ, Hertzberg VS, Frankel MR, Levine SR, Chaturvedi S, Kasner SE, Benesch CG, Sila CA, Jovin TG, Romano JG (2005) Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 352(13):1305–1316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043033

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174

Marzewski DJ, Furlan AJ, St Louis P, Little JR, Modic MT, Williams G (1982) Intracranial internal carotid artery stenosis: longterm prognosis. Stroke 13(6):821–824

Craig DR, Meguro K, Watridge C, Robertson JT, Barnett HJ, Fox AJ (1982) Intracranial internal carotid artery stenosis. Stroke 13(6):825–828

Klijn CJ, Kappelle LJ, Algra A, van Gijn J (2001) Outcome in patients with symptomatic occlusion of the internal carotid artery or intracranial arterial lesions: a meta-analysis of the role of baseline characteristics and type of antithrombotic treatment. Cerebrovasc Dis 12(3):228–234

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) Investigators (1991) Clinical alert: benefit of carotid endarterectomy for patients with high-grade stenosis of the internal carotid artery. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Stroke and Trauma Division. Stroke 22(6):816–817

Moustafa RR, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Jones PS, Graves MJ, Fryer TD, Gillard JH, Warburton EA, Baron JC (2010) Watershed infarcts in transient ischemic attack/minor stroke with > or =50% carotid stenosis: hemodynamic or embolic? Stroke 41(7):1410–1416. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.580415

Goldstein LB, McCrory DC, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Ancukiewicz M, Oddone EZ, Matchar DB (1994) Multicenter review of preoperative risk factors for carotid endarterectomy in patients with ipsilateral symptoms. Stroke 25(6):1116–1121

Rothwell PM, Slattery J, Warlow CP (1997) Clinical and angiographic predictors of stroke and death from carotid endarterectomy: systematic review. BMJ 315(7122):1571–1577

Cohen JE, Gomori J, Grigoriadis S, Lylyk I, Ferrario A, Miranda C, Rajz G (2008) Single-staged sequential endovascular stenting in patients with in tandem carotid stenoses. Neurol Res 30(3):262–267. doi:10.1179/016164107X230793

Tsutsumi M, Kazekawa K, Tanaka A, Aikawa H, Nomoto Y, Nii K, Sakai N (2003) Improved cerebral perfusion after simultaneous stenting for tandem stenoses of the internal carotid artery—two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 43(8):386–390

Gock SL, Mitchell PJ, Field PL, Atkinson N, Thomson KR, Milne PY (2001) Tandem lesions of the carotid circulation: combined extracranial endarterectomy and intracranial transluminal angioplasty. Australas Radiol 45(3):320–325

Homburg PJ, Plas GJ, Rozie S, van der Lugt A, Dippel DW (2011) Prevalence and calcification of intracranial arterial stenotic lesions as assessed with multidetector computed tomography angiography. Stroke 42(5):1244–1250. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596254

Marquering HA, Nederkoorn PJ, Smagge L, Gratama van Andel HA, van den berg R, Majoie Ch B (2011) Performance of semi-automatic assessment of carotid artery stenosis on CT angiography: clarifications of differences with manual assessment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol (in press)

White JH, Bartlett ES, Bharatha A, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, Thompson AL, Bitar R, Symons SP (2010) Reproducibility of semi-automated measurement of carotid stenosis on CTA. Can J Neurol Sci 37(4):498–503

Berg M, Zhang Z, Ikonen A, Sipola P, Kalviainen R, Manninen H, Vanninen R (2005) Multi-detector row CT angiography in the assessment of carotid artery disease in symptomatic patients: comparison with rotational angiography and digital subtraction angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 26(5):1022–1034

Zhang Z, Berg M, Ikonen A, Kononen M, Kalviainen R, Manninen H, Vanninen R (2005) Carotid stenosis degree in CT angiography: assessment based on luminal area versus luminal diameter measurements. Eur Radiol 15(11):2359–2365. doi:10.1007/s00330-005-2801-2

Zhang Z, Berg MH, Ikonen AE, Vanninen RL, Manninen HI, Zhang Z, Berg MH, Ikonen AEJ, Vanninen RL, Manninen HI (2004) Carotid artery stenosis: reproducibility of automated 3D CT angiography analysis method. Eur Radiol 14(4):665–672

Woodcock RJ Jr, Goldstein JH, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, Phillips CD (1999) Angiographic correlation of CT calcification in the carotid siphon. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 20(3):495–499

Hong NR, Seo HS, Lee YH, Kim JH, Seol HY, Lee NJ, Suh SI (2011) The correlation between carotid siphon calcification and lacunar infarction. Neuroradiology 53:643–649. doi:10.1007/s00234-010-0798-y

Taoka T, Iwasaki S, Nakagawa H, Sakamoto M, Fukusumi A, Takayama K, Wada T, Myochin K, Hirohashi S, Kichikawa K (2006) Evaluation of arteriosclerotic changes in the intracranial carotid artery using the calcium score obtained on plain cranial computed tomography scan: correlation with angiographic changes and clinical outcome. J Comput Assist Tomogr 30(4):624–628

de Weert TT, Cakir H, Rozie S, Cretier S, Meijering E, Dippel DW, van der Lugt A (2009) Intracranial internal carotid artery calcifications: association with vascular risk factors and ischemic cerebrovascular disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 30(1):177–184. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A1301

Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M Jr, Detrano R (1990) Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 15(4):827–832

Ewe SH, Ng AC, Schuijf JD, van der Kley F, Colli A, Palmen M, de Weger A, Marsan NA, Holman ER, de Roos A, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ, Delgado V (2011) Location and severity of aortic valve calcium and implications for aortic regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol 108:1470–1477. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.007

Saba L, Sanfilippo R, Montisci R, Mallarini G (2010) Assessment of intracranial arterial stenosis with multidetector row CT angiography: a postprocessing techniques comparison. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31(5):874–879. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A1976

Ptak T, Hunter GH, Avakian R, Novelline RA (2003) Clinical significance of cavernous carotid calcifications encountered on head computed tomography scans performed on patients seen in the emergency department. J Comput Assist Tomogr 27(4):505–509

Lee J (2011) Coronary artery calcium scoring and its impact on the clinical practice in the era of multidetector CT. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. doi:10.1007/s10554-011-9964-5

Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, Sheedy PF, Schwartz RS (1995) Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation 92(8):2157–2162

Schmermund A, Denktas AE, Rumberger JA, Christian TF, Sheedy PF 2nd, Bailey KR, Schwartz RS (1999) Independent and incremental value of coronary artery calcium for predicting the extent of angiographic coronary artery disease: comparison with cardiac risk factors and radionuclide perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 34(3):777–786

van der Bijl N, Joemai RM, Geleijns J, Bax JJ, Schuijf JD, de Roos A, Kroft LJ (2010) Assessment of Agatston coronary artery calcium score using contrast-enhanced CT coronary angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 195(6):1299–1305. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.3734

Venema HW, Hulsmans FJ, den Heeten GJ (2001) CT angiography of the circle of Willis and intracranial internal carotid arteries: maximum intensity projection with matched mask bone elimination—feasibility study. Radiology 218(3):893–898

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bleeker, L., Marquering, H.A., van den Berg, R. et al. Semi-automatic quantitative measurements of intracranial internal carotid artery stenosis and calcification using CT angiography. Neuroradiology 54, 919–927 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-011-0998-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-011-0998-0