Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Stronger cellular adhesion on the surface of endovascular devices promotes accelerated healing of aneurysms. The purpose of this in vitro study was to study the cellular interaction on the surface of bioactive Guglielmi detachable coils (GDCs) after using the surface-modification technology, ion implantation.

METHODS: Polystyrene (PS) dishes and platinum plates were used to simulate a GDC surface. They were treated with either simple collagen coating or collagen coating followed with ion implantation. Bovine endothelial cells (2–2.5 × 104 cells in 1 mL) were suspended in medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum on the PS dishes or platinum plates. Five days after cell seeding, the strength of cell adhesion was evaluated by trypsin treatment and flow shear stress. The cell detachment from the PS and platinum surfaces was observed microscopically.

RESULTS: Five days after cell seeding, both simple collagen-coated surfaces and collagen-coated ion-implanted surfaces showed uniform endothelial proliferation. After trypsin treatment, or under flow shear stress, stronger cell adhesion against chemical and flow shear stress was observed on the ion-implanted collagen-coated surface. In contrast, the endothelial cells were detached easily from the non-ion-implanted collagen-coated surface.

CONCLUSION: Ion implantation in combination with protein coating improves the strength of surface cell adhesion when exposed to flow shear stress and proteolytic enzymes. Strong endothelial cell adhesion is reported to be important to achieve earlier endothelialization across the neck of an embolized aneurysm with bioactive GDCs. This new technology may improve long-term anatomic outcome in cerebral aneurysms treated with GDCs.

The use of Guglielmi detachable coils (GDCs) for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms has been developed to offer a less traumatic and more controllable approach to aneurysm occlusion via the endovascular route (1, 2). Although GDC technology has some advantages over conventional surgery, it also has some limitations for the treatment of some intracranial aneurysms. One limitation is that GDCs appear to be less anatomically effective for wide-necked or large-to-giant aneurysms (anatomic limitation) (3–5). In these types of aneurysms, GDC technology often fails to achieve early control of the aneurysm inflow. Complete and permanent aneurysm occlusion may not occur. GDCs tend to be inert biologically and promote a limited and delayed inflammatory response and scar formation in aneurysms (biological limitation). Further geometric and biological modifications of GDC technology are necessary to improve present anatomic and clinical results in the endovascular therapy of cerebral aneurysms.

Recent human histologic studies in the literature describe limited, organized thrombus formation and lack of endothelial cell proliferation in aneurysms treated with GDCs (6–9). These results probably are related to an incomplete coiling of the GDCs in the aneurysm combined with a limited biological cellular response elicited by the coils in the aneurysm.

The analysis of interaction of cells, extracellular matrix, and biomaterials plays an important role in biomedical applications. Many studies have shown that cellular adhesion tends to correlate with the surface free energy and surface charge of intravascular devices (10, 11). This concept has led to the development of different physical and chemical methods to modify the surface characteristics of intravascular devices to elicit a favorable cellular response on their surfaces (12, 13).

A current technical approach to improve cellular attachment on the surface of an intravascular device relies on surface protein adsorption by protein coating (14–16). The anchorage of cells to a protein-coated surface, however, is not durable with simple coating methods. Simple protein coating may not be strong under mechanical stress that occurs with coil delivery through microcatheters or with high flow shear stress at the orifice of an aneurysm, and it also may be a potential source of thromboembolic complications to the cerebral circulation.

To achieve a stronger cellular adhesion and to promote accelerated wound healing in aneurysms, we have used the combination of ion-implantation technology with various protein coatings on the surfaces of platinum coils (17). This ion-implantation process creates a “borderless” interface between the coated protein and platinum surface by embedding the protein into the platinum surface.

The purpose of this in vitro study was to evaluate the differences in cellular interaction on the surface of a potential intravascular device, comparing standard protein coating to protein coating combined with ion-implantation technology.

Methods

Special attention was paid to the evaluation of the strength of cellular adhesion on the material surface against chemical (trypsin treatment) and mechanical (flow shear) stresses. These experiments simulated the GDC surface at the neck of an aneurysm when exposed to blood proteolytic enzymes and flow sheer stress.

Ion implantation is a physico-chemical surface-modification process resulting from the impingement of a high-energy ion beam (18). When ion implantation is performed on protein-coated materials, the proteins are mixed and embedded into a metallic structure (mixing effect). Ion implantation can create a borderless surface with modified chemical and electrical characteristics that may improve endothelial cell adhesion and control surface thrombogenicity. Recently, this technology has been applied to the surface modification of polymers to improve their blood compatibility (12, 13).

An in vitro study was performed to evaluate the effect of ion implantation on endothelial cell adhesion to a protein-coated GDC surface. Polystyrene (PS) dishes and thin platinum plates were used. Transparent PS dishes were used for continuous observation of cell proliferation and adhesion using phase-contrast microscopy. Nontransparent platinum plates were used for evaluation of cellular adhesion or detachment or both. The plates were evaluated with scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Trypsin Test for Cell Adhesion and Cell Detachment

Protein Coating and Ion Implantation

The surface of PS dishes and platinum plates (2 cm × 2 cm) was divided into two areas. In area A, the protein coating was performed without the ion-implantation technique. Area B included 100 μm of circular areas in which protein coating was followed by ion implantation.

Both areas A and B were coated with type I collagen (bovine dermis collagen, 0.3%; Koken, Tokyo, Japan). Then, Ne+ implantation was performed on area B with fluxes of 1 × 1015 ions/cm2 at an energy of 150 keV at room temperature. The beam current density used was lower than 0.5 μA/cm2 to prevent an increase in the specimen temperature. Figure 1 is a schematic view of the controlled ion-implantation process on a collagen-coated platinum surface. The ion-implantation area was regulated by 100 μm circular masks.

Schematic diagram of surface modification by ion implantation to protein-coated material surface. Surface of PS dishes and platinum plates was coated with type I collagen. Ne+ implantation was performed on an area that was regulated by a 100 μm circular mask.

Cell Migration, Adhesion, and Proliferation

Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) were isolated from the descending aorta by an adaptation of the method of Jaffe et al (19), with minor modifications. Endothelial cells (2–2.5 × 104 cells in1 mL) were suspended in medium (RPMI-1640, Nissui Pharm Co., Tokyo) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum on the PS dishes. The cells were incubated for 5 days in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. During the incubation periods, the extent of cellular adhesion and proliferation were determined visually on successive days with an optical microscope and transmission electron microscope. Endothelial cell culture was performed on platinum plates in the same fashion except that the cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde each day and observed using SEM.

Strength of Endothelial Cell Adhesion

Five days after cell seeding, the resistance to cell detachment was evaluated by trypsin treatment. Trypsin (0.125%) (Difco, MI) was dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and placed in contact with the endothelial monolayer, which was seeded on the PS dishes and platinum plates for 2 minutes at 25° C. The trypsin solution then was removed, and cells were rinsed once with PBS prior to microscopic observation and cell counting. Then cell detachment from the surface of PS dishes or platinum plates was observed microscopically.

Flow Shear Stress Test

BAECs were cultured on the collagen-coated PS dishes and collagen-coated ion-implanted PS dishes for 5 days. These dishes were exposed to laminar flow in a parallel plate-flow chamber (Fig 2). The lower plate of the chamber with two inlet-outlet slits (1 × 20 mm) was made of transparent polymethylmethacrylate. The liquid flow path was formed by inserting a silicone rubber gasket between the lower plate and a PS-coated slide glass on which BAECs were confluently cultured. The thickness of the gasket used was 0.3, 0.5, or 1.0 × 10−3 m, defined as a height (h) of the flow path. The BAECs cultured slide glass was mounted in a polymethylmethacrylate fixture, which was fixed to the lower plate by using eight screws. The width (w) and length (l) of the flow path were 22 and 72 × 10−3 m, respectively. One percent PBS was introduced from a reservoir to the inlet of the chamber through a pump (type FJ, Haake Gebrueder, Berlin, Germany). The temperature of the PBS was maintained at 37°C in the reservoir. The volumetric flow rate Q (m3s−1) was calculated from the time required to fill a 100 mL graduated cylinder. One-dimensional laminar flow was obtained in the flow path. The wall shear stress τw (Pa) is calculated from  where μ is the medium viscosity (Pa s), which was set at 0.69 × 10−3 (viscosity of water at 37°C) in this calculation. Two Pa were chosen to simulate arterial blood flow shear stress. The flow chamber was placed on the stage of a phase-contrast microscope (type EHT, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo). BAECs exposed to flow shear stress were photographed at intervals up to 3 hours. The number of adherent cells in an area of 0.36 mm × 0.36 mm was determined by counting cells in the micrograph. Five samples were subjected to histologic investigation at each time. All values are expressed as the mean ± SD. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and probabilities less than .05 were considered significant.

where μ is the medium viscosity (Pa s), which was set at 0.69 × 10−3 (viscosity of water at 37°C) in this calculation. Two Pa were chosen to simulate arterial blood flow shear stress. The flow chamber was placed on the stage of a phase-contrast microscope (type EHT, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo). BAECs exposed to flow shear stress were photographed at intervals up to 3 hours. The number of adherent cells in an area of 0.36 mm × 0.36 mm was determined by counting cells in the micrograph. Five samples were subjected to histologic investigation at each time. All values are expressed as the mean ± SD. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and probabilities less than .05 were considered significant.

Schematic diagram of parallel plate-type flow chamber used for applying flow shear stress to endothelial cells cultured on PS surface. PS-coated slide glass on which endothelial cells (BAECs) were confluently cultured was mounted together with a silicone rubber gasket to a lower PMMA plate. Flow shear stress was imposed on BAECs by circulating 1% PBS maintained at 37°C in reservoir by using pump.

Results

Trypsin Test for Cell Adhesion and Cell Detachment

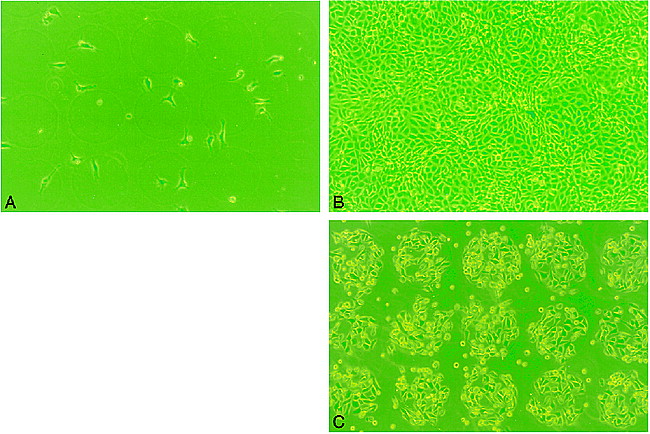

Figure 3A–B shows phase-contrast microscopic observations of proliferation of cultured BAECs on the area A (collagen-coated PS) and area B (collagen-coated ion-implanted PS) after 1 day and 5 days of seeding. The BAECs cultured on both areas A and B showed intense proliferation and confluence at day 5. There was no remarkable difference between the two areas. After the trypsin treatment, however, the cells in area A easily detached from the surface. Most cells detached from the surface within 2 hours. In contrast, most endothelial cells remained on area B (with ion implantation), demonstrating a strong surface adhesion (Fig 3C).

Phase-contrast micrograph of BAECs on PS surface patterned by ion implantation (original magnification, ×100; diameter of a circle, 100 μm).

A, Day 1, no endothelial proliferation was observed on either protein-coated only (area A) or ion-implanted protein-coated (area B) surface.

B, Day 5, areas A and B demonstrated uniform proliferation of the BAECs.

C, Day 5, Post-trypsin treatment at 2 hours. Note most of BAECs were strongly attached on the ion-implanted circular area. Almost no BAECs were observed on surface coated with collagen only.

Similar results were observed on the platinum plate study. Figure 4A–B showed an SEM appearance of cell proliferation and detachment on the platinum plates with or without ion implantation.

Scanning electron micrograph of BAECs on platinum plate patterned by ion implantation. (Note morphologic deformity of cells owing to effect of trypsin and glutaraldehyde.)

A, Day 5, areas A and B demonstrated uniform proliferation of BAECs.

B and C, Note strong BAEC adhesion only on circular ion-implanted protein-coated areas (original magnification, ×100 [for B]; ×400 [for C]).

Flow Shear Stress Test

Five days after cell culture on the two different surfaces (collagen-coated only and collagen-coated ion-implanted), both surfaces showed homogeneous, confluent cell proliferation. After exposure to a flow shear stress at 2 Pa, 29% of BAECs cultured on the simple collagen-coated PS were detached within 30 minutes after imposition of shear stress. In contrast, almost no BAECs cultured on the collagen-coated ion-implanted PS surface were detached after exposure to a flow shear stress (simple coating, 1943 ± 73 cells; ion implanted, 2635 ± 106 cells). After 150 minutes, 82% of cells still were attached on the ion-implanted protein-coated PS surface (2258 ± 41 cells) and 67% of cells were attached to the simple protein-coated surface (1875 ± 348 cells), signifying a statistically significant difference (Fig 5).

Sequential changes in number of endothelial cells exposed to flow shear stress: 30 min (P < .001), 45 min (P < .001), 60 min (P < .05), 90 min (P < .01), 150 min (P < .05), 180 min (P = .1488).

Discussion

Biological Characteristics of the GDC

Although the use of GDCs represents a rapid expansion of the endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms, long-term efficacy of the GDC for wide-neck aneurysms or large-to-giant aneurysms remains unsatisfactory. Limited case reports in the literature emphasizing clinical histopathologic findings report a minimal inflammatory and endothelial cell response over the neck of the aneurysms (6–9). Neointima coverage over the neck of an aneurysm is histologic proof of a complete cure of the aneurysm. Therefore, appropriate biological modifications of the GDC surface may improve endothelial cell proliferation and promote an acceleration of wound healing across the neck of the aneurysm. These histologic changes might anchor the GDCs in place and decrease the possibility of aneurysm recanalization.

Tamatani et al (16) have studied the in vitro endothelial cell growth on platinum coils and protein-coated platinum coils. They reported a marked improvement in the degree of cell proliferation on the coated coils compared with the non-coated platinum coils.

Kalmes et al (20, 21) demonstrated a new method using genetically modified fibroblasts on GDCs. They also reported an improvement of cellular proliferation on modified coils with protein coatings. These studies have shown improvement of the cell proliferation and migration on the modified GDCs in vitro. Although these preliminary results encourage clinical use of this methodology, there are some discrepancies that need to be analyzed. The major limitations of these in vitro studies are the lack of analysis of the effect of flow dynamics on endothelial cell proliferation and the affect of proteolytic enzymes in blood.

Ion Implantation Technology

Ion implantation is one surface-modification technique that requires high-energy ion beams (18). This technology has been used for improving the surface properties of metals, such as wear and corrosion resistance. The implantation energy used in metal modification is several hundred keV to MeV. Recently, ion implantation has been applied to polymer modification to improve its biocompatibility (12, 13, 22). The expended energy in polymer modification ranged between 50–200 keV. When ion implantation is performed on a protein-coated surface (50–150 keV), proteins are embedded and mixed into the platinum surface. The newly created surface does not lose its original mechanical properties.

This in vitro study confirms that the protein-coated ion-implanted surface improves the endothelial cell resistance to proteolytic enzymes and flow shear stress when compared with a standard protein-coated surface. Figure 6 shows the difference in cellular interaction between a protein-coated surface versus an ion-implanted protein-coated surface. With standard protein coating, endothelial cells can attach to the coated protein surface, but this attachment is indirect to the substriate surface. Although the strength of cell adhesion to coated protein may appear to be strong, the interface between coated protein and material surface may not be strong enough to resist flow shear stress. Conversely, endothelial cells attach directly to the material surface when treated by ion-implantation technology. An ion-implanted protein-coated surface does not have an interface between the surface material and the coated protein, allowing a stronger direct cellular attachment between the endothelial cell and the surface of the material and stronger resistance to blood flow shear stress.

Transmission electron micrograph of BAECs on polystyrene dish. Both simple collagen-coated surface and collagen-coated ion-implanted surface demonstrate BAECs attachment.

A, Note thickness of coated collagen on simple coating surface (large arrow). Detachment of cell-collagen complex may appear to occur from interface between coated collagen and PS surface (small arrow).

B, On the other hand, direct cell adhesion was observed on ion-implanted collagen-coated PS surface.

Shear Stress and Aneurysm

The flow shear rate of blood at the wall of a small artery has been found by calculation, assuming laminar flow to be more than 700 s−1. Kawamoto et al (23) reported that endothelial cells covering the inner surface of a vascular graft need to resist a flow shear stress of at least 2 Pa. Kamiya et al (24) reported shear stress levels in the arterial system ranged from 10–20 dynes/cm2 (10 dynes/cm2 = 1 Pa), an approximate mean of 15 dynes/cm2.

Recently, the flow shear stress on an aneurysm wall also was analyzed by several investigators (25–28). Steiger et al (27, 28) evaluated in vitro flow shear stress of cerebral aneurysms with terminal and lateral side-wall models. They estimated that maximum shear stress on the wall of human terminal and side-wall aneurysms was 50 dynes/cm2 (5 Pa). We do not have adequate data on the intensity of flow shear stress occurring at the neck of an embolized aneurysm with GDCs (especially of those with a small neck remnant). Nonetheless, at least 2 Pa may be necessary to simulate the flow shear stress of an embolized cerebral aneurysm.

A limitation of this in vitro study relates to the technical difficulty of continuously monitoring endothelial cell detachment from trypsin treatment when using platinum plates. The cultured endothelial cells showed morphologic deformity after trypsin or glutaraldehyde treatment. The phase-contrast microscope could not be used for the platinum-plate study because platinum is not transparent. Therefore, PS dishes were used to simulate a platinum surface. Once ion implantation was performed on a protein-coated (substriate) surface, however, the surface characteristics of ion-implanted protein were basically the same, regardless of differences of substrates.

Conclusion

Ion implantation, in combination with protein coating, improves the strength of surface cell adhesion when exposed to flow shear stress and proteolytic enzymes. Strong endothelial cell adhesion appears to be important for achieving earlier endothelialization across the neck of an embolized aneurysm with GDCs. Such strong cellular interaction also may minimize untoward cerebral thromboembolic complications. These in vitro results suggest that ion-implanted protein-coated GDCs may improve long-term anatomic outcome of the intracranial aneurysms in general, and of large wide-neck aneurysms in particular.

Footnotes

↵1 Address reprint requests to Yuichi Murayama, MD, Division of Interventional Neuroradiology, Department of Radiological Sciences, UCLA School of Medicine and Medical Center, 10833 Le Conte Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024, U.S.A.

References

- Received February 9, 1999.

- Copyright © American Society of Neuroradiology