Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging has been used successfully to identify post-treatment recurrence or postoperative changes in rectal and cervical carcinoma. Our purpose was to evaluate the usefulness of dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging for distinguishing recurrent inverted papilloma (IP) from postoperative changes.

METHODS: Fifteen patients with 20 pathologically proved lesions (recurrent IP, 12; fibrosis or granulation tissue, eight) were enrolled in the study. Three observers, blinded to pathologic results, independently evaluated conventional MR images, including T1-weighted (unenhanced and postcontrast), proton-density–weighted, and T2-weighted spin-echo images. Results then were determined by consensus. Dynamic images were obtained using fast spin-echo sequences at 5, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, and 300 seconds after the injection of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid. Time-signal intensity curves of suspected lesions were analyzed by a pharmacokinetic model. The calculated amplitude and tissue distribution time were used to characterize tissue, and their values were displayed as a color-coded overlay.

RESULTS: T2-weighted images yielded a sensitivity of 67%, a specificity of 75%, and an accuracy of 70% in the diagnosis of recurrent IP. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images yielded a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 50%, and an accuracy of 65%. Pharmacokinetic analysis showed that recurrent IP had faster (distribution time, 41 versus 88 seconds) and higher (amplitude, 2.4 versus 1.2 arbitrary units) enhancement than did fibrosis or granulation tissue. A cut-off of 65 seconds for distribution time and 1.6 units for amplitude yielded a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 100% for diagnosing recurrent IP.

CONCLUSION: Dynamic MR imaging can differentiate accurately recurrent IP from postoperative changes and seems to be a valuable diagnostic tool.

Inverted papilloma (IP) is a common neoplasm of the nasal cavity. This benign epithelial neoplasm usually arises within the nasal vault and, less commonly, in the paranasal sinuses. Patients typically present with nasal obstruction, epistaxis, or nasal discharge. Surgical intervention usually provides a favorable outcome. There is, however, a high rate of recurrence (15%−78%) associated with IP (1−6). When symptoms recur, a biopsy is necessary to confirm the recurrence of IP. Because complete en bloc excision is necessary for treatment of a recurrent tumor, a precise preoperative diagnosis is beneficial for surgical planning. Biopsy may be unreliable, however, as sampling errors can occur because of the chronic inflammation surrounding sinonasal neoplasms (1−4). Furthermore, endoscopic examination cannot access several critical areas such as the frontal sinus, fovea ethmoidalis, cribriform plate, superior-lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus, and medial-inferior wall of the orbit (1, 4, 5).

MR imaging has been used to evaluate sinonasal IP (7). Yousem et al (7) found that IP lesions usually show intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Postoperative imaging of IP becomes more complicated because repair with granulation and fibrosis occurs after surgery. Nevertheless, dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging with pharmacokinetic analysis has been used successfully to distinguish recurrent tumors from postoperative changes in various diseases (8−10). Therefore, in this retrospective study, we tested the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging with pharmacokinetic analysis in distinguishing recurrent IP from postoperative inflammatory changes (fibrosis or granulation tissue).

Methods

Patients

Our observations were based on 16 MR imaging examinations of 15 patients (14 men and one woman; age range, 34−70 years) with 20 suspected recurrent IP lesions. One patient had undergone two MR imaging examinations after two operations, respectively (Table 1). Four patients each had two suspected lesions. All patients had histories of surgical treatment for sinonasal IP, 13 by lateral rhinotomy and medial maxillectomy, and three by functional endoscopic surgery. MR studies were performed because of the clinical endoscopic or CT findings of soft-tissue lesions in the nasal cavity or paranasal sinus or both. Biopsy specimens for histologic evaluations were obtained by lateral rhinotomy and medial maxillectomy (12 patients), functional endoscopic surgery (two patients), or both separately (one patient). The median interval between surgery and MR examination was 11.5 months (range, 5−60 months).

Characteristics, imaging results, and final diagnoses of patients with suspected recurrence of inverted papilloma

Imaging Schemes

All images were obtained with a 1.5-T imager with a quadrature head coil. Conventional MR studies were performed in the axial and coronal planes. T1-weighted images were obtained with parameters of 600/20/2 (TR/TE/excitations). Long TR images with or without frequency-selective fat saturation were obtained with 2200−3000/18−36/1 (proton-density [PD]-weighted) and 2200−3000/80−108/1 (T2-weighted). The matrix size was 256 × 192, and the section thickness was 5 mm. Postcontrast T1-weighted images with or without frequency-selective fat saturation were acquired in the coronal and axial planes after dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging.

Dynamic MR images were obtained using the fast spin-echo technique and the following parameters: 400/17/1 (TR/effective TE/excitations); echo train length, 4; matrix, 256 × 192; field of view, 24 × 18 cm; and section thickness, 5 mm. This technique yields an imaging acquisition time of 15 seconds and four sections, positioned at the level where the main part of the lesion has been identified on the unenhanced image. The injection was performed through a 20-gauge catheter inserted in an antecubital vein before the start of the study. The dynamic images (0 seconds) were obtained before the bolus injection of the contrast agent. Dynamic imaging was repeated 5 and 30 seconds after rapid manual bolus injection (2 mL /second) of 0.1 mmol of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid/kg of body weight followed by a 10-mL flush of normal saline (time zero was the end of the flush). Imaging then was performed every 30 seconds during the first 180 seconds and at 300 seconds. Thus, a total of nine sets of dynamic images were obtained. Conventional MR and dynamic MR images first were reviewed independently by three radiologists who were blinded to the histologic diagnosis. The three reviewers were in agreement on the diagnosis in all cases.

MR Image Analysis

For conventional MR imaging, the MR images were evaluated for signal intensity and contrast enhancement pattern according to the methods presented by Yousem et al (7). Before contrast enhancement, the signal intensity of the lesions was compared with that of fat, muscle, and CSF in T1-, PD-, and T2-weighted images. After contrast enhancement, the lesions were assessed for their homogeneity and degree of enhancement as compared with the nasal turbinate mucosa. Enhancement was classified as marked (enhancing as much as that of mucosa), moderate (definite enhancement but not as striking as that of mucosa), or mild (slight increase over baseline signal intensity after the administration of contrast agent, much less than that of mucosa). We developed criteria adapted from a previous report (7) for the diagnosis of IP. IP lesions were defined as appearing hypointense relative to CSF and hyperintense relative to muscle on T2-weighted images and as showing mild to moderate inhomogeneous enhancement after the administration of contrast agent. Postoperative changes (ie, granulation or fibrosis) were defined as appearing iso- to hyperintense relative to CSF on T2-weighted images and as showing marked enhancement after the administration of contrast agent (11, 12).

For dynamic MR imaging, to obtain the time-signal intensity curves, regions of interest (ROIs) were placed within the 20 suspected lesions by one reader who had no knowledge of the final pathologic diagnosis. The size of the ROIs that was chosen in a lesion varied with the size and shape of the suspected lesion that appeared in the nine sets of images. Once determined, the ROI was consistently used to determine the mean signal intensity in the nine sets of images. The change in the signal intensity of an ROI placed on the mouth-floor muscle was used for reference. The relative signal increase (RSI) then was calculated as Scm (t)/S0, where Scm (t) = postcontrast signal at time t, and S0 = unenhanced signal. We used a three-parameter mathematical model for pharmacokinetic analysis, as described by Brix et al (13) and Greenstein et al (14): RSI (t) = 1 + A [1 − exp (−t / Tc)] − Ct, where RSI (t) = postcontrast signal at time t divided by the unenhanced signal, A = amplitude of enhancement, Tc = distribution time (time constant for arrival of contrast material), and C = first-order washout rate. The pharmacokinetic parameters A, Tc, and C were calculated by means of a nonlinear least-squares fitting program written in Matlab software. Because the signal intensity and the distribution time of uptake of contrast media are described mainly by A and Tc, we focused our pharmacokinetic analysis on these two variables for tissue characterization of recurrent tumors and postoperative changes.

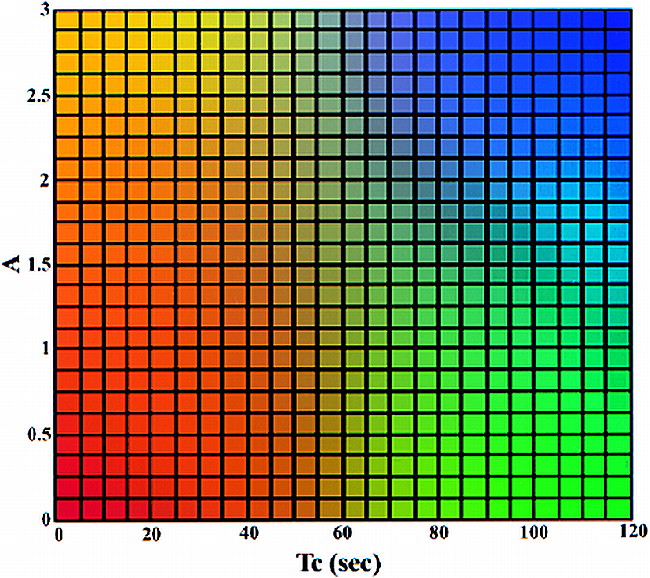

For further processing, the pharmacokinetic imaging data sets were transferred to a workstation. To reduce the number of images and facilitate visual interpretation, a color-coding table (Fig 1) was applied that used a reference matrix to overlay color-coded parameters of both amplitude and distribution time. Overlaying the color-coded parameters on the conventional images allows the functional information regarding the contrast medium enhancement to be combined with the corresponding morphologic images. To automate this approach, we developed a software package to process the dynamic images on a pixel-by-pixel basis for each section. The software program mainly consists of six components: 1) an MR image format transformation, 2) a motion correction module, 3) an ROI boundary detection module, 4) a quantitative evaluation module, 5) a quantitative evaluation of dynamic MR data, and 6) a color representation of ROI. The automated data processing requires approximately 30 minutes and can be performed in a clinical setting.

Two-dimensional color table. The value of the amplitude (A) is from 0 to 3 and that of the distribution time (Tc) is from 0 to 120. The four-corner colors of the color table are yellow, red, blue, and green. The colors of other elements are generated using bilinear interpolation according to their position on the color table. The color mapping of the ROI is determined on the basis of the value of A and Tc in each pixel. Note that at values above 3, A is set to 3; at values above 120, Tc is set to 120

Statistics

The MR image readings were analyzed to evaluate the relationship between different diagnoses. We used Student's t test (for equal variances) or Wilcoxon rank sums test (for unequal variances) to compare the RSI of recurrent neoplasms and post-treatment inflammatory tissues at different time periods. The dynamic MR imaging data for the lesions were tested retrospectively using Student's t test and a two-sample Wilcoxon test for the difference in the values of the pharmacokinetic parameters. After the lesions were classified, their mean pharmacokinetic parameter values of amplitude and distribution time were displayed in a two-dimensional scatter plot. The criteria selected to determine optimal threshold values on the scatter plot were the greatest overall accuracy and low rate of false-positive results (8). Finally, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the discriminatory power of each of the criteria, the signal intensity on T2-weighted images, the postcontrast studies, and the dynamic contrast imaging were calculated.

Results

Conventional MR Imaging

Classification of the lesions on the basis of the signal intensity on T2-weighted images resulted in two of eight postoperative changes in lesions being misclassified as recurrence and four of 12 recurrent lesions being misclassified as postoperative changes. This yielded a sensitivity of 67%, a specificity of 75%, and an accuracy of 70%. For the contrast studies, four of eight postoperative changes in lesions were misclassified as recurrences and three of 12 recurrent lesions were misclassified as postoperative changes. This yielded a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 50%, and an accuracy of 65% (Table 2).

Efficacy of signal intensity on T2-weighted images and postcontrast T1-weighted images for detecting recurrent inverted papilloma

Dynamic MR Imaging

Figure 2 shows the time-signal intensity curves of recurrent tumors and postoperative changes. The signal intensities of both postoperative changes and recurrent IP increased to a similar final magnitude, but there were marked differences in relative enhancement immediately after contrast injection. Statistical analysis revealed a significantly higher RSI in recurrent tumors than in postoperative changes at 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 seconds (P < .01).

RSI indices (mean ± 1 standard error) for recurrent IP (open bullets), postoperative changes (solid bullets), and mouth-floor muscle (inverted pyramid) are shown. Note the differences in the magnitude and time course of enhancement. Both types of lesions enhance to a similar final magnitude, but there are marked differences in relative enhancement immediately after contrast injection (P < .01 by Student's t test or Wilcoxon rank sums test)

Two representative cases that illustrate the diagnostic usefulness of the dynamic scan are presented in Figures 3 and 4. Pharmacokinetic analysis showed that recurrent tumors had higher amplitude of enhancement (amplitude, 2.4 ± 0.7 [mean ± SD] arbitrary units) than did postoperative changes (1.2 ± 0.4 arbitrary units) (P = .0005, Wilcoxon test). In addition, recurrent tumors showed shorter distribution times of contrast enhancement (41 ± 18 seconds) than did postoperative changes (88 ± 23 seconds) (P = .0012, Wilcoxon test).

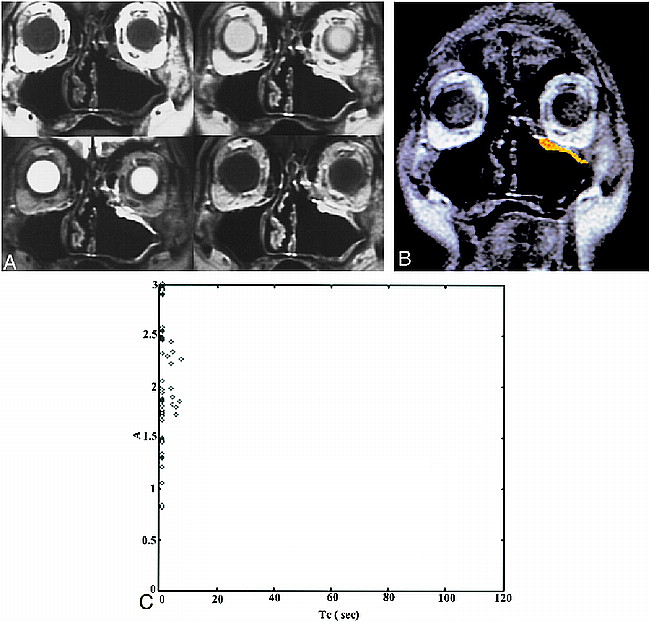

A case of postoperative recurrent IP. Patient 2 was referred because of the presence of a polypoid mass in the left superior maxillary sinus wall. This patient had a left nasal fossa IP, which was initially treated with en bloc excision by lateral rhinotomy-medial maxillectomy 15 months before the study was conducted.

A, Conventional MR images (upper left, T1-weighted image [600/20/2]; upper right, PD-weighted image [2500/18/1]; lower left, T2-weighted image [2500/90/1]; lower right, postcontrast T1-weighted image). The T1-weighted image shows isointensity with muscle. The T2-weighted image shows an area of homogeneous hyperintensity in the left superior maxillary sinus wall; the signal intensity is isointense to CSF. Postcontrast studies show homogeneously marked enhancement as compared with enhanced mucosa. The diagnosis of the conventional images is “postoperative changes.”

B, ROI analysis shows a color-coded image suggestive of recurrence.

C, Two-parameter scatter diagram shows amplitude (A) plotted against the distribution time (Tc). The A and Tc of the pixels corresponding to the ROI are shown.

Analyzing the scatter plots of the pharmacokinetic parameters, we found that selecting a threshold amplitude of 1.6 units yielded a diagnostic accuracy of 95% (sensitivity, 100%; specificity, 88%), whereas selecting a distribution time of 65 seconds yielded an accuracy of 90% (sensitivity, 100%; specificity, 75%). By combining the two thresholds, we were able to discriminate recurrent tumors from postoperative changes in all cases (sensitivity, 100%; specificity, 100%) (Table 3) (Fig 5).

Efficacy of pharmacokinetic parameters for differentiating recurrent tumors from postoperative changes

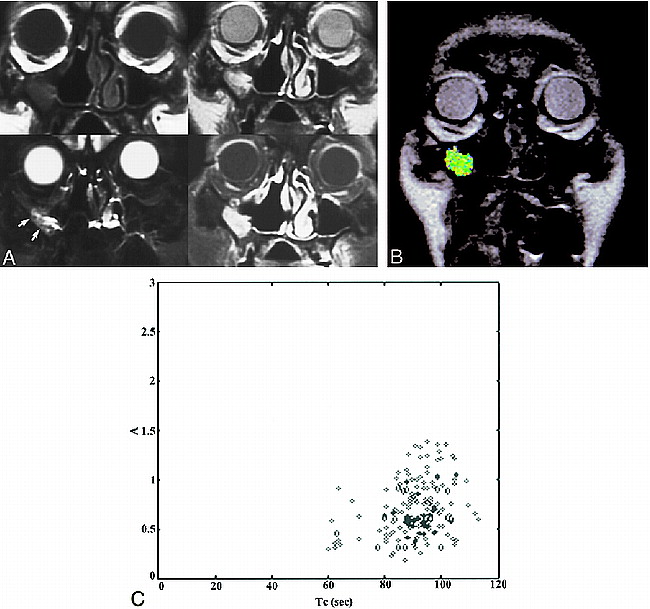

A case of postoperative changes. Patient 6 was referred because of the presence of a polypoid mass in right maxillary sinus wall. This patient had a right nasal fossa and maxillary sinus IP that was treated initially with en bloc excision via lateral rhinotomy-medial maxillectomy 9 months before the study was conducted.

A, The conventional images are presented in the same order as those shown in figure 3A. The T1-weighted image shows isointensity to muscle. The T2-weighted image shows a region of inhomogeneous hyperintensity in right maxillary sinus wall; the signal intensity of most areas (arrows) in this region is hypointense to CSF and hyperintense to muscle. Postcontrast studies with fat saturation show inhomogeneous, moderate enhancement as compared with enhanced mucosa. The diagnosis of the conventional images is “recurrence.”

B, ROI analysis shows a color-coded zone suggestive of postoperative changes.

C, The A and Tc of the pixels corresponding to the ROI are shown.

Two-parameter scatter diagram showing amplitude (A) plotted against the distribution time (Tc). The recurrent IP (diamonds) are localized in the left upper corner, displaying a combination of high amplitude and short distribution time. Tumor recurrence can be defined by a combination of amplitude greater than 1.6 arbitrary units and distribution time less than 65 seconds. The postoperative changes (solid bullets) are characterized by low amplitude (<1.6 arbitrary units) and long distribution time (>65 seconds). Only one postoperatively changed lesion displayed high amplitude. In this case, the lesion still can be distinguished from a recurrent tumor on the basis of distribution time; however, if only the amplitude were considered, the lesion would be misclassified as a tumor

Discussion

We have found that dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging has greater sensitivity and specificity than does conventional MR imaging for discriminating recurrent tumors from postoperative changes after surgical resection of IP. Recurrent tumors had higher amplitude and shorter distribution time than did postoperative changes.

Several recent studies have attempted to differentiate lesions of the sinonasal cavity by means of MR imaging signal intensity characteristics and enhancement patterns. Most sinonasal tumors have intermediate signals on T2-weighted images (7, 11, 12, 15). In contrast, T2-weighted images of inflammatory processes predominantly show bright signal intensity, often as bright as that of mucosa or CSF (7), reflecting the rich water content caused by interstitial edema, serous fluid, or mucous secretions. Such characteristics have been found in mucosal inflammation, retention cysts, mucoceles, and polyposis (11, 15, 16) and help T2-weighted images to distinguish sinonasal tumors from inflammatory tissues in most cases (15, 16). Furthermore, T2-weighted images can also delineate the tumor boundaries with the surrounding inflammatory tissue.

Postoperative imaging of IP is, however, a complicated and time-consuming procedure. During the immediate postoperative period after surgery, the dominant healing reaction is active inflammation with a high water content. Nevertheless, once fibrosis becomes a significant component of the maturing postoperative reaction, the combined low signal intensity of the scar tissue and the bright signal of any active inflammation results in an overall tissue signal of an intermediate intensity on T2-weighted images and enhancement on postcontrast images (15). As such, this tissue cannot be differentiated confidently from recurrent tumor (Fig 4). In this study, we found that some recurrent tumors had bright T2-weighted signal intensities and showed changes similar to those of inflammatory tissues (Fig 3). We postulated that this was caused by tumor in combination with postoperative changes. The results of our T2-weighted and postcontrast imaging studies thus showed a lower accuracy. Therefore, differentiating a recurrent tumor from granulation tissue or scarring in a postoperative patient is always problematic with conventional T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced imaging.

The usefulness of pharmacokinetic analysis of contrast enhancement using a two-compartment model has been repeatedly successful in identifying post-treatment conditions such as rectal carcinoma and cervical carcinoma (8−10). The distribution time is a tissue-specific transport parameter that describes the velocity of contrast medium transfer between the plasma compartment and the interstitium of the lesion. This parameter is influenced by regional blood flow and vascular permeability. Lesions such as recurrent IP have a short distribution time, which is an indication that they harbor high-grade vascularity or endothelial permeability or both. Our finding that tumors have significantly shorter distribution time values than postoperative changes support theories that tumors harbor vascularity and large openings in the endothelium because of damage of the basement membranes of tumor vessels (17).

The amplitude, which describes the degree of contrast enhancement, is mainly influenced by the interstitial volume. The influence of the native relaxation time is negligible because tumors and postoperative changes have similar values. We did not find any reports in the literature on the use of MR imaging for evaluating the interstitial space of IP. Nonetheless, published data (18, 19) suggest that the interstitial space of other tumors is significantly larger than that of normal tissue, allowing more space for the transport and accumulation of contrast agent molecules. Additionally, a study by Nugent and Jain (20) showed quantitatively that the interstitial space for the transport of molecules in granulation tissue is considerably smaller than that in neoplastic tissue.

This study has several limitations. First, the fast spin-echo, dynamic MR sequence, although less susceptible to artifacts than a fast gradient-echo sequence, is limited by the number of sections per scan (four sections per scan in the present study). This limitation may result in a false-negative result, erroneously excluding recurrence because of incomplete coverage of the entire sinus. Second, because all 16 examinations were performed at least 5 months after surgery, the results presented herein may not be explicitly applied to patients who undergo IP surgery less than 5 months before MR examination. Furthermore, the enhancement pattern of the nasal turbinate is similar to that of recurrent tumors, which may cause difficulty in delineating the inferior margin of a contacting mass. Finally, the reliability of our high values for the efficacy of dynamic MR imaging is limited by the reliance on retrospectively, rather than prospectively, selected criteria for optimal threshold values. We need to use these criteria prospectively to test a large series of patients in the future.

In conclusion, our study has shown that MR imaging, in combination with conventional and dynamic contrast-enhanced sequences, is a good follow-up technique after surgical resection of IP. Dynamic MR imaging can help discriminate recurrent tumors from postoperative changes. At a minimum, MR imaging can provide valuable information regarding what sites should be targeted for biopsy.

Footnotes

↵1 Supported by grants from NSC 87-2314B-075B-003 and VGHKS 87–46.

Presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology, Philadelphia, May 1998.

↵3 Address reprint requests to Ping H. Lai, MD, Department of Radiology, Veterans General Hospital-Kaohsiung, 386 Ta-Chung First Rd, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 813.

References

- Received October 26, 1998.

- Accepted after revision April 26, 1999.

- Copyright © American Society of Neuroradiology